Versione italiana dell’intervista disponibile qui.

Edited by Virginia Stefanini

This current issue of Libri Calzelunghe focuses on series. Series are very popular among young readers: they experience the pleasure of meeting the same familiar elements book after book. In narrative series readers want to know what will happen to the main characters and how the story will end. But series are not exclusively fictional, and we have many examples of nonfiction series. Approaching a nonfiction series, readers experience a different link.

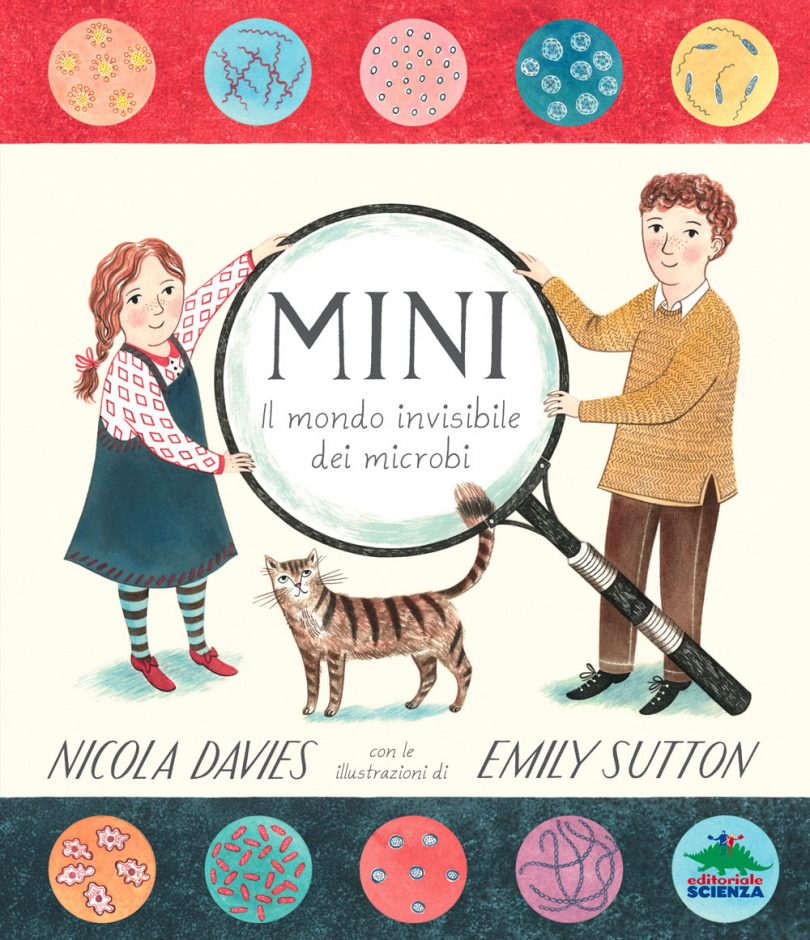

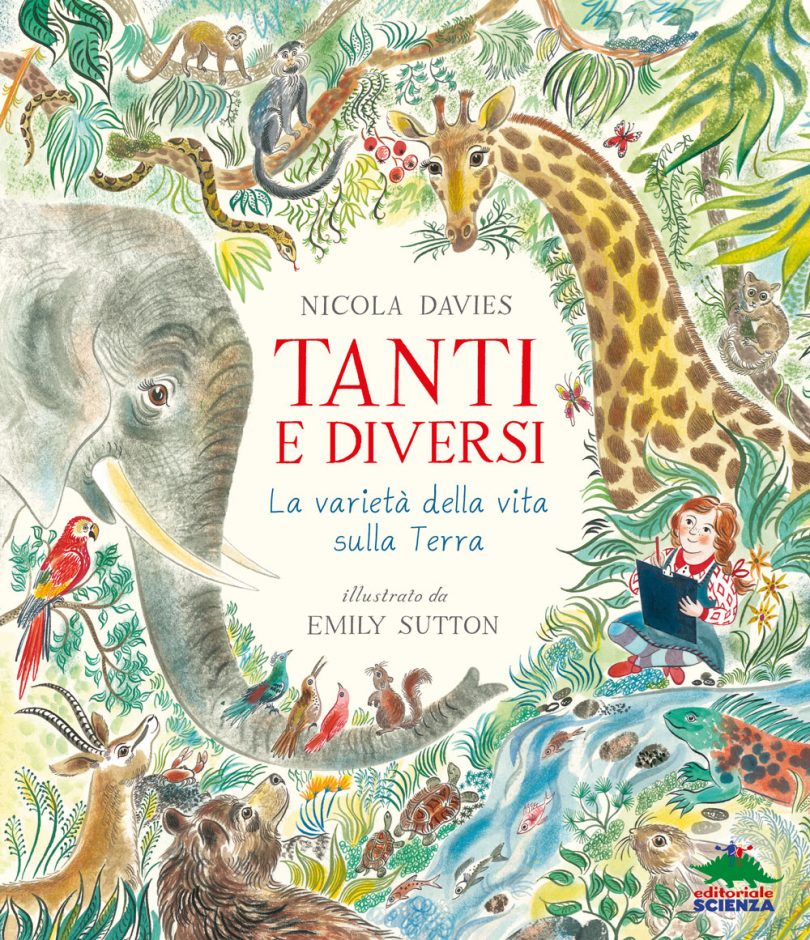

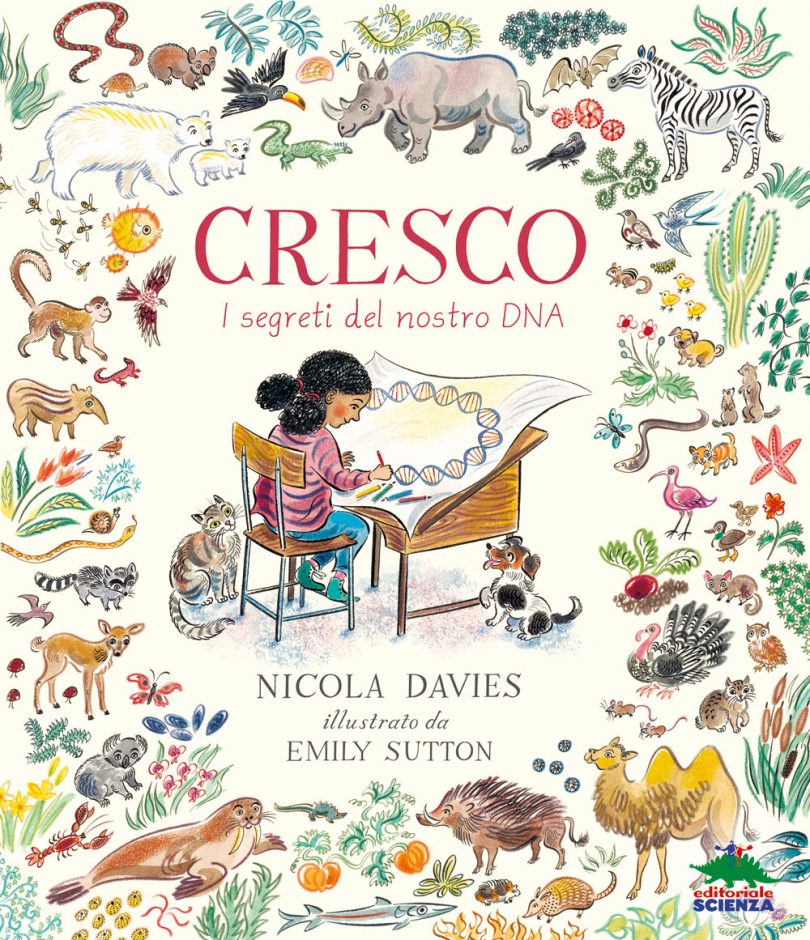

As an author, Nicola Davies created several nonfiction series of books, from ironic Animal Science to poetic A First Book of Nature / Animals / Sea, and other series that mix fiction and nonfiction, like Heroes of the Wild or Silver Street Farm. Even her picture books Tiny, Lots and Grow can be considered a series in its own. We asked Nicola Davies to talk about books and series.

Libri Calzelunghe: According to your experience, what makes a series of books work or not?

Nicola Davies: It depends on whether its fiction or non-fiction. With fiction you need a cast of characters whose relationships and abilities can evolve through a number of different stories; you need a setting that gives the opportunity for multiple plots, and you need to introduce new characters as the series progresses.

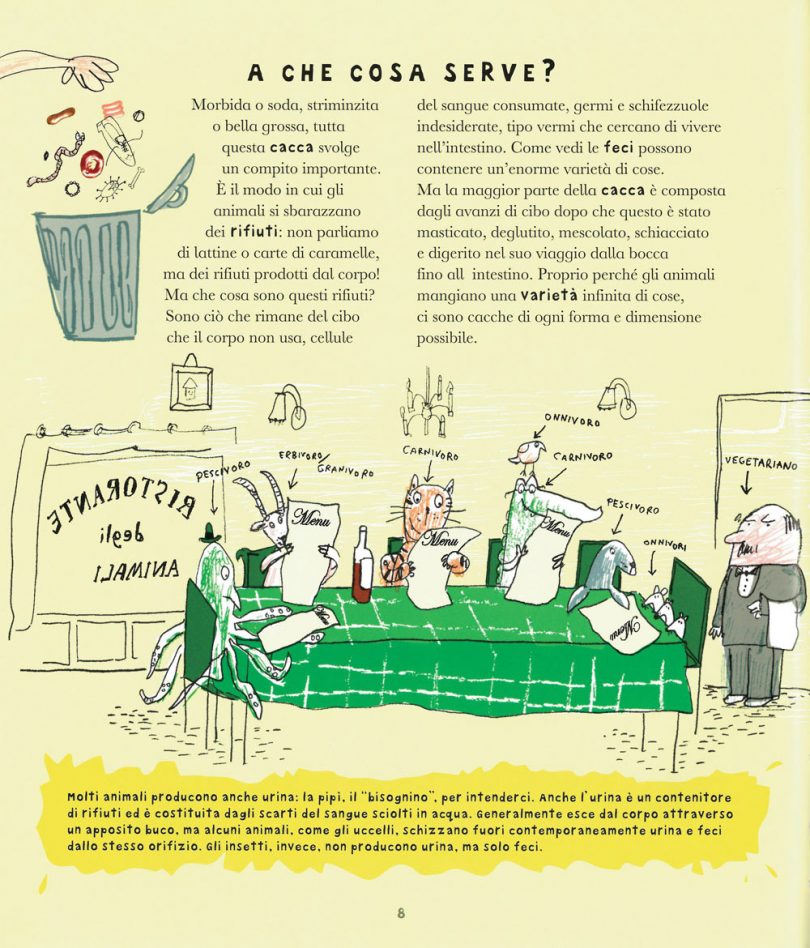

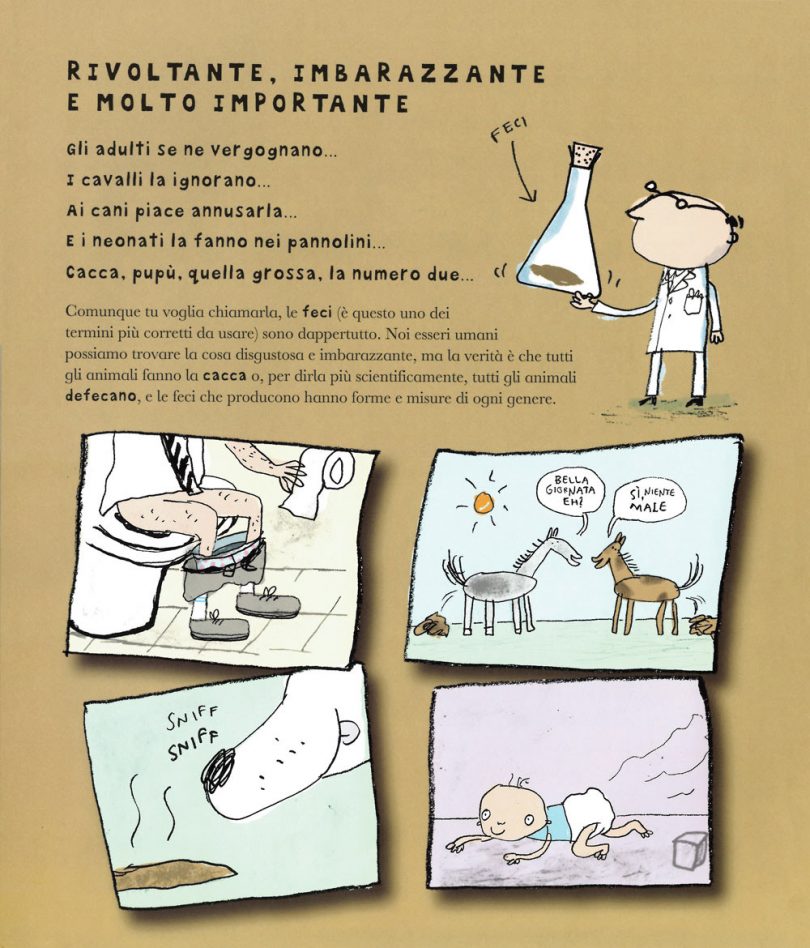

With non-fiction, it’s about a consistency of approach and tone. In the Animal Science series I took a series of big, complex topics in biology – actually things that would be covered by a whole module of lectures at university – and presented them in a chatty enthusiastic voice. Of course illustration is key – Neal Layton’s amazing style, which is so rich in information and humour was perfect and I was able to write for Neal’s illustrative voice.

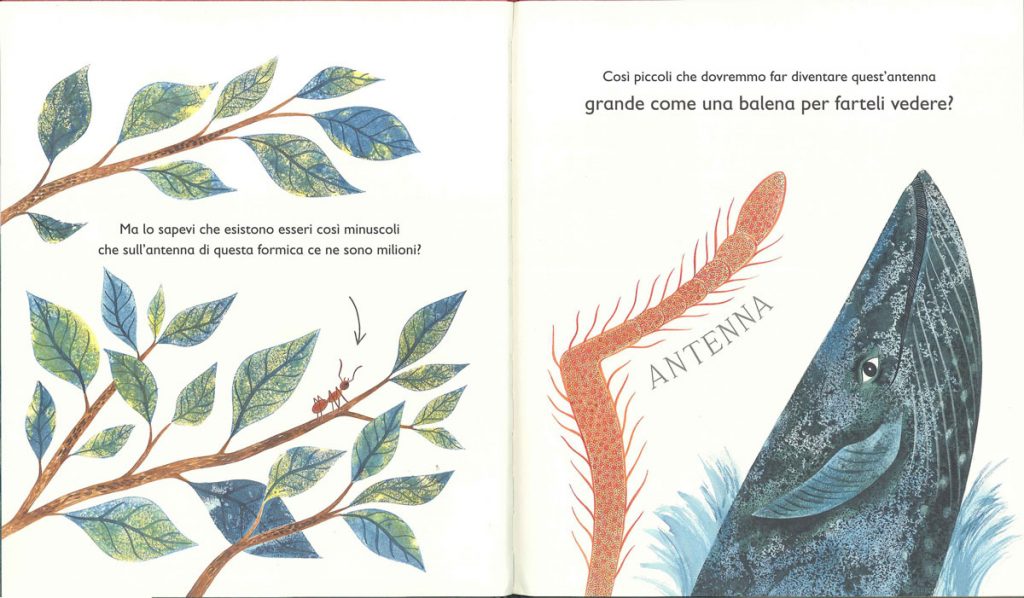

Tiny, Lots and Grow are entirely different – I wanted to present big ideas but distill them into a simple easy to understand form. So they were much, much harder to write. The problem with condensing is that as you cut the words you change the meaning. That’s why a poetic, conceptual approach with the language is so important, that way it’s possible to embody meaning in the combination of imagery in the words and the illustration. Emily Sutton’s style is perfect for this approach; every aspect of those illustrations is underpinned with science, they are full of precise information.

LC: And where your creative process especially starts from: a format, a character, a topic or other?

ND: Again, that’s rather dependent on the fiction non-fiction divide. Generally of course with non-fiction it’s the topic. But for me the approach, the ‘how’ of the writing is very closely connected to the ‘what’. Decisions about format come much later, when I have a sense of what the illustration requires and in conversation with illustrator and designer. With fiction it’s usually a character that I have clear image of in my head, that alerts me to a story that is wanting to be told. With Heroes of the Wild, all the stories were so closely based on reality that they were largely retellings of the real life accounts that I gathered from interviewing people in the locations where the books are set. There was with some of the stories very little actual invention of plot. Often all I had to do was change the protagonist from an adult into the child, and put together incidents that had happened to several different people so that they happened to my child protagonists. If you look in the real world there are stories just lying about, waiting for you to pick them up and tell them.

LC: Kids love series for their peculiar narrative perspective. And creating a narrative in non-fiction texts is the aim of many of your books. Which is your idea about the traditional opposition between fiction and nonfiction in children’s books?

ND: For me, narrative is the most important thing. So although the starting point for fiction and non-fiction is somewhat different, the process of narrative creation is not so different between genres. A narrative requires a beginning, a middle and an end, it requires a narrative voice, a narrator, a perspective. All these decisions are the same in fiction and non-fiction. The only real difference is that finding the right narrative voice and the right narrative thread is much MUCH more difficult with non-fiction than with fiction.

LC: Your picture books Tiny, Lots and Grow have many things in common, beginning from the contribution of illustrator Emily Sutton. In these books we follow the young characters through the pages in their discovery of Nature around and inside them. In Tiny and Lots we meet the young girl with braids and striped socks and her friend; in Grow, a large family with five kids. None of them have a name or a personal story, but they appear in almost every page, so we become curious about who they are! Can you tell us more about these characters, and which is their role in your books?

ND: Those characters are entirely Emily’s invention! I love the way they are un-named, unmentioned in the text, because they give the reader the chance to identify with them and to tell their own stories about them. Picture book creation is deeply collaborative, deeply rooted in mutual respect. I trust Emily’s creative decision making, so after an initial conversation about the text, and my providing her with exact visual references, I know I can relinquish control and let her tell her side of our story.

LC: You are a prolific author. Your audience is composed of readers of different ages, from babies to middle graders, and your work too is a mixture of different styles: you wrote picture books and expository books, narrative non-fiction and novels, in rhyme and prose. What you always do in all your books is using precise words and very accurate definitions of the natural world. How important the language is to describe animals, plants and scientific phenomena?

ND: Precision in the use of language is a slight obsession of mine – partly born out of my scientific training and the use of Latin names, that in themselves impart all kinds of scientific information. But also comes from my exposure to poetry and the sound and atmosphere of words as a child. Individual words can carry huge power, not only as tools for conveying information but for colouring the emotion of the reader. I want my texts to connect with readers intellectually and emotionally, so the way I use words is very carefully controlled to achieve that.

LC: Before becoming a children’s author, you have been a zoologist and a tv presenter for BBC. How much these two former professions influence your writing?

ND: Being an academic zoologist showed me that I didn’t want to simply ‘preach to the choir’, I didn’t want to speak to a small academic audience; I wanted to change the world! Working in TV and writing factual TV series for children taught me about brevity and precision, and how to choose the best story to grab children’s attention.

LC: Do you think stories can influence the relationship between new generations and Nature?

ND: I really hope so! I really believe so. Stories are old. Humans have been telling stories almost before we were human. I’m certain early hominids told stories. So they ARE the way we interpret and understand the world, process out own experiences, share information. We need more kinds of stories told and a greater diversity of voices, and we need to listen to the stories that other species have to tell, and not be quite so obsessed with what our species has to say.

Many thanks to Nicola Davies for her time and willingness and to her italian publisher Editoriale Scienza for collaboration.

[…] delle serie. Intervista a Nicola Davies, a cura di Virginia Stefanini (articolo isponibile anche in inglese) Ancora una storia! Sulla serialità nei libri per ragazzi, di Guido […]

[…] English version of this interview available here. […]